Has Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine Produced a Zeitenwende? A SAIS Retrospective

Jacob Levitan

Edited by Alexandra Huggins

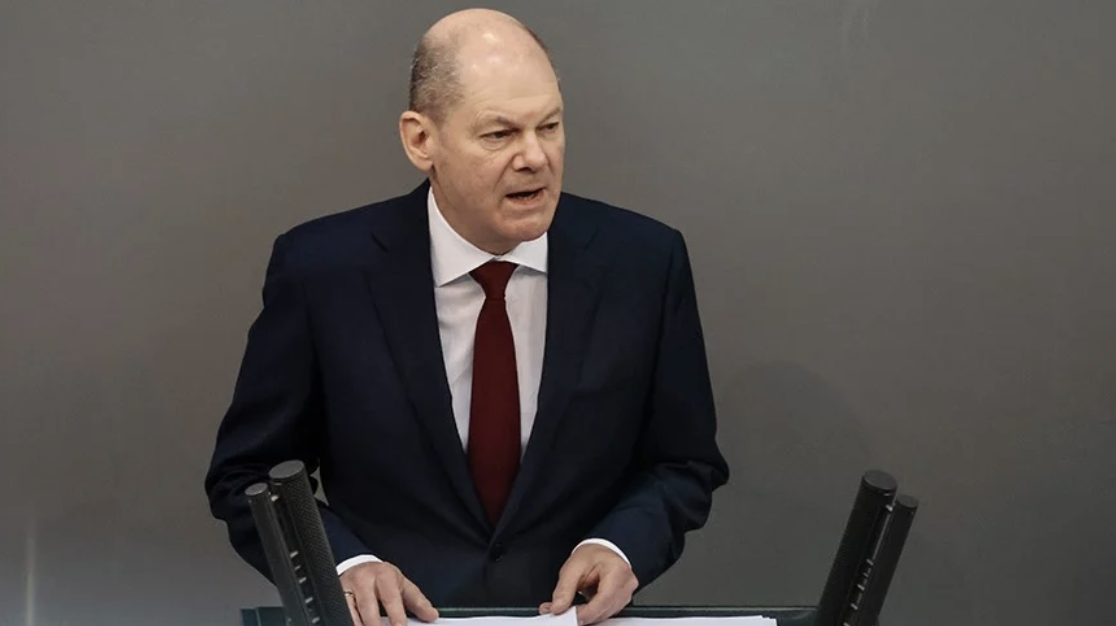

Fourteen months ago, on February 27, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced to the German parliament, the Bundestag, that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine three days prior had marked a Zeitenwende, or a watershed moment. Stunning the world, Chancellor Scholz declared an injection of 100 billion Euros into Germany’s ailing military, the Bundeswehr, and a pledge to immediately allocate 2 percent of Germany’s GDP to the defense budget. As the SAIS Class of 2023 prepares to graduate, it seems fitting to determine whether this class will graduate into a world significantly altered by a Zeitenwende.

It is important to understand that both Putin and Scholz hoped for a Zeitenwende. Putin launched his so-called “Special Military Operation” not just to forcibly reincorporate Ukraine into his neo-Russian Empire, but to dismantle the US-led, rules-based world order based on principles of democracy, free markets, the rule of law, and human rights. For Scholz, the war would lead to a reevaluation of Germany’s, and Europe’s, strategic cultures.

When Putin launched his “operation,” he assumed his forces would encounter a welcoming population and easy victory, resetting the world order. When the war began, I wrote for this publication – erringly – arguing the prevailing wisdom that Russia’s troops – while suffering extraordinarily heavy casualties from a hardened Ukrainian force – would reach Kyiv within weeks and that Putin had, by launching his invasion, “shot” the US-led world. Thankfully, the Ukrainians’ unyielding resolve and love for freedom, supported by Western arms, has taught Mr. Putin a costly lesson.

Still, Scholz was not proven right just because Putin was proven wrong. Germany has made progress but has yet to fulfill the promised Zeitenwende. Sophia Besch, a fellow for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Europe Program, noted at the SAIS Europe and Eurasia event “Zeitenwende? The Future of German Defense after Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine” that Chancellor Scholz broke with several core German policy beliefs – on Russia, energy, and defense – during his Zeitenwende speech.

Prior to the invasion, Germany’s Russia policy was predicated on engagement. Berlin believed, even as Moscow repeatedly broke its promises, that a mutually beneficial (if asymmetrical) relationship between Germany (and Europe) and Russia could be achieved “Scholz broke with these assessments in his speech,” Ms. Besch said. His new political coalition – the SDP, the Green Party, and the conservative Economic Liberal Party immediately came about in support of his new approach. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock of the historically pacifist Green Party, argued that the “world has changed, so our politics have to change too” in, as Ms. Besch observed, a reversal of the German axiom “never again war from Germany.”

Germany has succeeded in decoupling its energy from Russia, but its defense record remains disappointing. While Scholz and the Bundestag approved the 100-billion-euro special fund to end the Bundeswehr’s deplorable condition, hardly a cent of the fund has been spent. As Ms. Besch noted, Germany’s “procurement bureaucracy is only able to spend 9 billion euros per year [and] there is a lack of necessary personnel in the Bundeswehr.”

Berlin has proceeded with $8.83 billion plans to acquire 35 F-35s for the Luftwaffe – its air force – with deliveries slated between 2026-2030 and has reaffirmed its NATO nuclear sharing agreements. However, no investments have been made in developing Germany’s – or Europe’s – defense-technology-industrial base (DTIB). Germany, like the rest of Europe, continues to rely on US military enablers – capacities that logistically enable missions – such as air-to-air refueling and heavy airlift. The Bundeswehr, crippled by a state of chronic unreadiness, is struggling to even maintain the military platforms US military enablers would support – and only $500 million has been spent to repair and upgrade 143 Puma infantry fighting vehicles.

Germany’s indecision towards Ukraine – particularly regarding the Polish Leopard 2 tanks – has also hurt the Zeitenwende’s fulfillment, encouraging doubt of Berlin’s sincerity among its friends and enemies. This was an example, Ms. Besch said, of Zusammenfuhren, or “leading from the middle.” From Berlin’s view, Germany was, by preventing Poland from shipping Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine until the United States agreed to send Abrams tanks, creating a consensus and a stronger front.

The Leopard 2 affair is representative of the greater challenge facing not just Germany, but Europe as a whole. The strategic culture in Germany and Europe is reactive, not proactive. The EU has haltingly sought to develop an independent military capacity and recently created a bloc-wide fund to incentivize the joint procurement of common military equipment, but only allocated 500 million euros to last until 2024.

Strategic autonomy – French President Emmanuel Macron’s brainchild for reducing European military dependency on the United States – has repeatedly run into European reticence, first to invest in defense, and now in a common European DTIB. But, as Ms. Besch argued, “if Europe wants autonomy tomorrow, you need to make the decision to invest wisely today.”

Indeed, the European defense budgets raised in response to the war in Ukraine have made investing the money not so much the issue – European military spending rose to $345 billion in 2022 compared to China’s $292 billion – as is using it wisely. Whereas the United States has four types of destroyers, one type of main battle tank, and six types of fighter jets, the Europeans have 29, 17, and 20 respectively. Such diversity of European military systems requires numerous supply chains procuring parts unique to each system, hampering military preparedness. The European failure to pursue necessary defense reforms has also led to doubt in the seriousness of the Zeitenwende I saw this doubt myself while at this year’s Munich Security Conference

While there, a German state-level official – who wished to remain anonymous – told me companies like Rheinmetall are not boosting production because they doubt the seriousness of the German – or European – governments’ intentions to build their defense capabilities. When I spoke with journalists and politicians at the Conference of strategic autonomy, the answers were either for it but without clear strategies for its realization, doubts about its feasibility, or dismissals of it being a cover for a “Greater France.” A standout moment of the Conference was, on the last day, when Radoslaw Sikorski – a former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland – publicly chastised Josep Borell – the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs – for the western member states letting Poland, without compensation, bear the brunt of supporting Ukraine against Russia.

So has a Zeitenwende occurred? As is often the case with such questions, it is yes and no. A significant change has occurred as Western European governments recognize Russia has, as their eastern neighbors warned for years, resurfaced as a security threat. The strategic cultures of countries like Germany and France require further recalibration but, given the history behind their pre-2022 strategic concepts, what has been accomplished in a year is remarkable. That Germany has both adopted its first-ever national security strategy and is organizing town halls across the country to popularize a proactive strategic culture is highly significant. However, European governments – Germany especially – still need to rapidly pass tough reforms targeting their defense manufacturing sectors and especially their procurement bureaucracies.

However, Chancellor Scholz promised a Zeitenwende that would change the world. A real Zeitenwende would have led to Europe adopting policies to create a European DTIB enabling it to emerge as a great power capable of global power projection. Instead, Europe has chosen a variation of the status quo ante, making the Europeans only stronger auxiliaries of the United States. A Europe capable of acting without US support thus remains highly unlikely in the near or medium term.

The SAIS Class of 2023 would do well to take note.